The term ‘Little friends’ was first coined by the USAAF 8th air force bomber crews during the Second world war. This came about when they were met by the Mustang and Thunderbolt fighters to escort them on their raids over Europe, supporting the success of the mission. This support from ‘Little friends’ can also be applied to Concorde. The project was so revolutionary, a number of smaller aircraft were used to test and research various aspects of the design to ensure the success of the mission to build a commercial supersonic airliner. This is the story of those test planes.

The original Royal Aircraft Establishment’s concept research into a supersonic transport can be traced back to the early 1950s. It was already known from previous research that the drag of a wing at supersonic speed was related to its span. However a small span wing produced very little lift at slow speed which would mean any plane built with this type of wing would need huge power and very long runways to get airborne. Thus a conclusion was reached that the wing design would make an SST an impractical proposition and the project was put on the back burner. However not long after this decision had been made, a further paper from the boffins at the RAE suggested that if the wing was extended along the fuselage as far as possible the vortices produced by the delta shape would give good lift at low speed. This design would be called the ‘slender delta’. The downside of this design however was that the aeroplane would have to land in a very nose high position to ensure sufficient lift could be obtained from the wing at slow speed. This problem required more research and as at the time the modern day super computers were not available, the old fashioned approach of building a test aircraft was undertaken. To explore the low speed characteristics of a wing of this shape Handley Page were awarded to contract to design a suitable aeroplane. They came up with the HP.115.

Design work on the research aircraft began in the 1950s but the first flight of the sole example of the HP.115 took place in August 1961. Powered by a single Bristol Siddeley Viper jet engine the aircraft featured a fixed undercarriage derived from the Jet Provost and wing leading edges made of plywood, the rationale behind this being different leading edge profiles could be easily fitted for further research. Of all the research aircraft built for the Concorde project the HP.115 had the longest career not being retired until 1974. It proved that the new shape of wing could provide safe handling right down to 69mph. At the end of its flying career it had flown almost to its design limit of 500 hours. It was retired eventually to the Fleet Air Arm museum at Yeovilton where it now sits alongside the British Concorde Prototype.

Design research on the slender delta wing continued at the RAE and eventually, for a number of reasons, the shape decided upon as the best for a supersonic transport aircraft was the ogee profile delta. A private contract was placed with NASA to modify a Douglas Skylancer to mimic this shape of wing. NASA 708 was suitably modified and in 1965 NASA would report that the ogival wing lowered the landing speed over the Skylancer’s normal delta wing. This airframe still exists awaiting restoration at the Evergreen Air and Space museum in the USA.

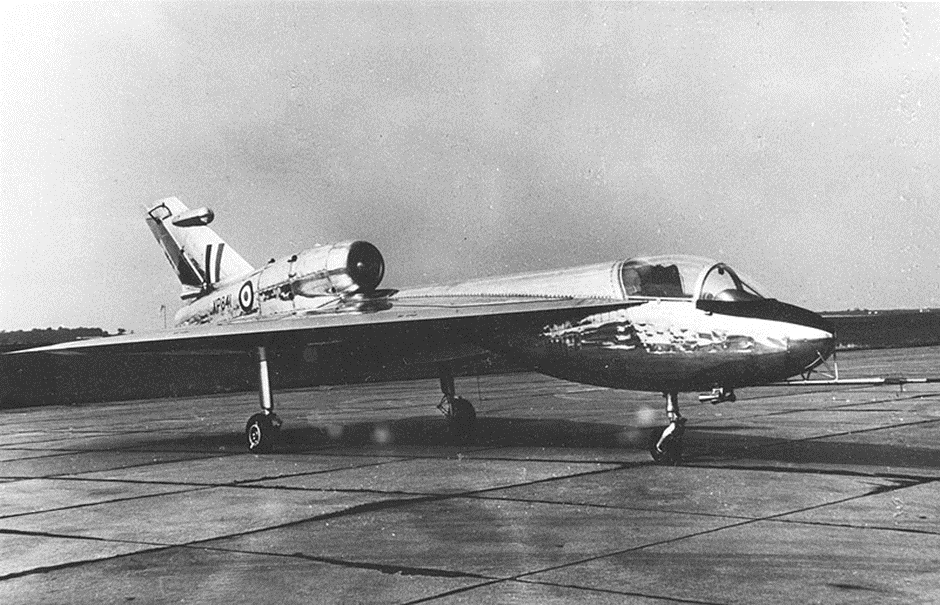

In parallel with the HP.115 testing the low speed flight regime, another aircraft was looking at the high speed end of the envelope. Fairey had built the Fairey Delta 2 to look into flight and control at transonic and supersonic speeds. First flying in October 1954, two flying examples would be built. Capable of exceeding 1000mph in level flight (the first aircraft to do so) in 1956 the Fairey Test pilot Peter Twiss set an absolute speed record of 1132 mph. Powered by a Rolls Royce Avon engine with reheat and with the nose drooping for better visibility during landing and take off the two aircraft supplied a large amount of data on high speed flight with a delta wing. When Fairey had finished their testing they handed both the aircraft over to the RAE to add to their test fleet of aircraft. Fairey had hoped to use the FD.2 as the basis for a supersonic fighter but this was never to happen.

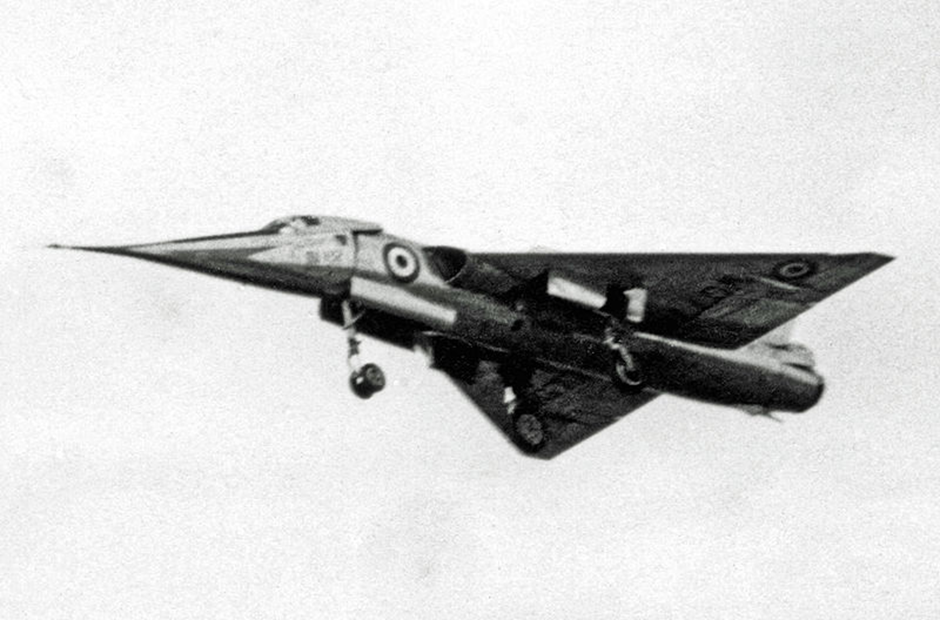

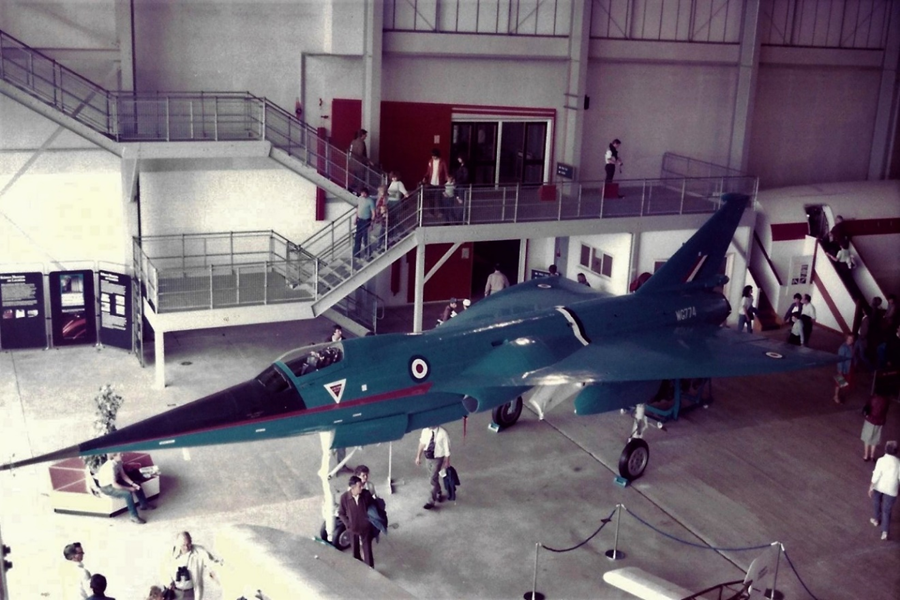

With flight research now needed into the ogival wing planned for Concorde, the RAE restarted talks with Fairey that had originally taken place place in 1958about modifying the FD.2 with a new wing to fulfil this role. Due to the re organisation of the British aircraft industry it wasn’t until 1960 that British Aircraft Corporation (BAC) started the project at its Bristol plant with one of the Fairey Delta 2s arriving at Filton in 1961 for the conversion. As well as the new wing, a longer undercarriage was fitted, the fuselage was made six feet longer, the engine intake was moved below the wing and larger fuel tanks were fitted. The modified aeroplane now known as the BAC 221 first flew in May 1964. All these modifications meant the new aeroplane could not match the speed of its predecessor but it still obtained Mach 1.6 during testing. Just one aircraft was built and after its test programme was complete, the BAC 221 was retired in 1973 and is now on display at Yeovilton.

With testing of the new ogival wing shape now covered by the HP.115 and the BAC 221 thoughts turned to what would be the best material to use in the build of the new supersonic airliner. It was well known that extended time at supersonic speed would cause the airframe to become very hot and it was for this reason standard aircraft grade Aluminium was thought not to be suitable. A research aircraft to test this heating effect had been commissioned in 1953 to trial materials for the planned Mach 3 reconnaissance aircraft, the Avro 730. Bristol had been awarded the contract and two aircraft known as the Bristol 188 were built to fly with an additional one built as a static test bed.

By 1957, with the Bristol 188 yet to fly, the Avro 730 was cancelled but the B.188 would still be built as a high speed research aircraft capable of flying at Mach 2. It wasn’t until 1962 that the first Bristol 188 took to the air having been built using new methods of construction such as Argon arc welding plus the use of titanium and stainless steel panels. To help keep the heat down the aircraft featured a very narrow fuselage and thin wing.

Although the aircraft was designed to fly at 1200 mph it never managed to reach Mach 2 and due to its very limited endurance flights could only last around 25 minutes, not really long enough for the true heating effects of prolonged high speed flight to be measured. Another problem was that the very small thin wing needed a take off speed of around 300 mph all of which hindered the test programme quite dramatically. The two aircraft only managed 70 flights between them before the project was abandoned in 1964. Some of the information gained was useful in the development of Concorde but most of the data was inconclusive. One of the aeroplanes was scrapped and the survivor is now in the RAF museum at Cosford. Concorde would eventually be built with a high temperature aluminium alloy known as Hiduminium RR 58 which it was calculated would be able to cope with the kinetic heating effects as long as Concorde’s speed was limited to Mach 2.02.

The final piece of the research jigsaw would be the afterburning Bristol Olympus engines which would be required to power Concorde supersonically. The Olympus engine was not new having first been run in 1950 and early versions were already in service on the Vulcan bomber fleet. Thus it was one of these aircraft that was chosen to be the test bed for the flight trials of the new variant.

The original Vulcan Olympus 101 had been developed into the afterburning Olympus 320 for the TSR2 which would first fly in 1964. As we all know this project was soon scrapped by the government but Rolls Royce (who had taken over Bristol engines) would further develop the engine into the Olympus 593 to power Concorde. This engine first ran in 1966. Like the engine in the picture above, a 593 was slung beneath a Vulcan for flight testing, the first flight of which was in September 1966. Sadly I have been unable to find any copyright-free pictures of this installation but if you are interested there are plenty of images available on line. In the Vulcan cockpit the aircraft Captain would fly the aeroplane, the co-pilot would control the test engine whilst in the back seats there would be two test engineers looking at the underslung engine’s performance and an Air Electronics Officer would be keeping an eye on the Vulcan’s systems.

All this testing by the ‘Little friends’ was put to good effect in the design of Concorde and the French prototype first flew on 2 March 1969, followed two months later by the British Prototype. The French aircraft continued its test programme until retirement in October 1973 whilst the British aeroplane appropriately registered G-BSST, flew on until March 1976 when it was retired and eventually put on public display at the Fleet Air Arm museum at Yeovilton. These prototypes were replaced in the test programme by two pre-production aircraft one of which, G-AXDN, we of course have here at Duxford in the British Airliner Collection. All in all Concorde has a lot for which to thank its ‘Little friends’.

‘till the next time Keith

Registered Charity No. 285809