The sleeping princesses

As a young boy, when we went on our ‘foreign’ holidays across the sea to the Isle of Wight, I always noticed the huge mummies on the dockside. My dad, who knew about these things, told me they were cocooned Princesses. For years I thought they were something from the Egyptian pyramids until he explained they were actually flying boats. This is the story of the sleeping princesses.

Large flying boats were nothing new, between the wars several amazing machines could be seen, none more so than the 12-engine Dornier Do-X. Powered initially by Bristol Jupiter engines made under licence by Siemens this huge triple-deck aeroplane was designed to carry up to 100 passengers on short flights or 60 across the Atlantic via several stops to New York. So large was this plane that the flight engineer, who controlled all 12 throttles on command of the Captain, had his own machine room to operate from. Only three examples of the Do-X were made, one for Lufthansa and two for operations in Italy by Italian airline SANA, these however were taken over by the Italian military. Both Italian aeroplanes were mothballed in 1935 and finally scrapped two years later.

Back in Germany the sole Lufthansa example was badly damaged when the tail snapped off during a botched landing in 1933. The aeroplane was patched up and flown back to Berlin where it was placed in a museum only to be destroyed in a RAF bombing raid in 1943.

In the UK Short brothers had been building flying boats for the military and Imperial Airways for many years and in 1936 they launched the large 24-seat Empire flying boat. These machines would serve Imperial and later BOAC for many years with Qantas and TEAL airlines also using them, the last Empire flying boat being retired in 1946. 42 examples were made and those operated by Imperial/BOAC were mainly used on the London to Africa and Australia routes. During the Second world war a number of Empire boats were pressed into use with the military but it was the Sunderland, developed from the Empire, which saw extensive military service.

The Empire boat was not built as a non-stop transatlantic aeroplane as it didn’t have the range unless fitted with ferry tanks, reducing its payload considerably. Finally Boeing company came up with a flying boat that could fly the US-UK route non- stop. That aeroplane was the Boeing 314 Clipper. First flying in 1938, 12 of these 24 seat planes provided the means to fly the Atlantic for the next ten years. Although all were ordered by Pan American World Airways they agreed to allow the final three to be sold to BOAC, as with the outbreak of war the BOAC Empire boats could no longer stop for fuel in Lisbon or Spain. The Pan Am machines not only flew the Atlantic but also the San Francisco - Hong Kong Pacific route as well. With the Second World War well underway the BOAC machines also plied the Atlantic crossing on behalf of the UK government or military. The Boeing Clipper would be the last large commercial flying boat made in the US.

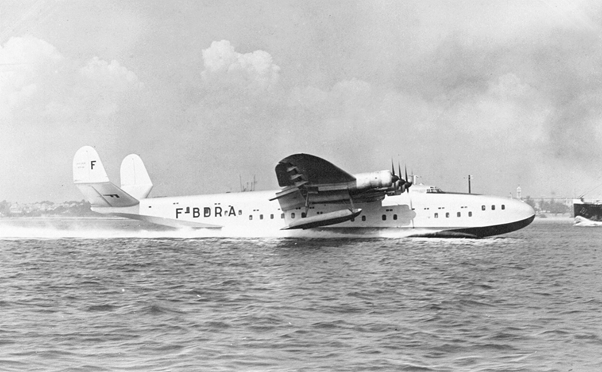

Back over this side of the Atlantic the French had also joined the large flying boat club with their Latecoere 631, a six-engine, 46-seat giant. First flying in 1942 the prototype was immediately pressed into service with the German Luftwaffe and flown to Lake Constance where it was destroyed two years later by RAF Mosquitos. The second, of a total of 11 built, first flew in 1945 and went into service with Air France who retired their fleet in 1948. The last Latecoere 631 was operated by Societe France Hydro and was finally grounded and scrapped in 1955.

Even after the end of the war when a large number of airfields became available around the world, Shorts still continued to build flying boats. In 1946 they flew a civilian successor to the Sunderland called the Short Solent. This aeroplane could carry up to 34 passengers and 16 examples were produced. Ordered by BOAC and TEAL of New Zealand, the BOAC machines were used on the Southampton to Johannesburg flight until 1950 when BOAC finally ceased flying boat services. Tasman Empire Airways Limited (TEAL) operated their five Solents until 1960 on flights between Sydney, Auckland, Fiji and Wellington. With many war surplus Sunderlands around Shorts started converting them into a civil aircraft called the Sandringham. BOAC flew some Sandringhams and the earlier Sunderland conversion, the Hythe. TEAL had also flown Sandringhams up to 1955 as did Qantas, retiring theirs the same year. The last operators of the type were Antilles Flying boats and Ansett Flying Boat Services who operated from Sydney to Lord Howe Island until 1974.

With the running down of flying boat services around the world it came as a surprise when in 1952 Saunders-Roe (also known as SARO) flew their Princess flying boat for the first time from their base in Cowes on the Isle of Wight. The UK government had placed an order in 1946 for three of these huge flying boats and planned for them to be operated by BOAC. As we have seen there were some large flying boats built in the past (we didn’t even look at the Spruce Goose) but the Princess is, to this day, the largest all-metal flying boat ever constructed with a gross weight of 147 tons and a wing span greater than a Boeing 747.

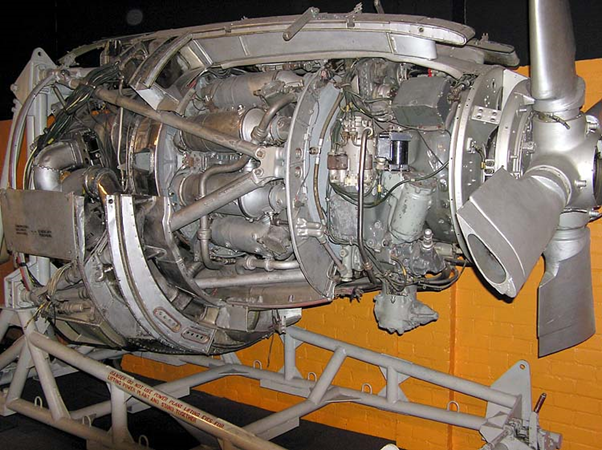

When more powerful engines became available it was hoped this great ship of the sky would be able to cruise at heights of up to 40,000 feet. SARO decided that to power a machine of this size capable of carrying 104 passengers they would need to use one of the new powerful turboprop engines being developed. They opted to use ten early-model Bristol Proteus engines to power their new flying boat. Eight of the engines would be mounted in pairs and drive contra-rotating twin propellers through a common gearbox and the other outer two engines would drive a conventional single propeller unit. Long delays in the development of this engine not only affected the Princess project but that of the Bristol Britannia as well.

Work had begun as soon as the order was signed but costs and delays began to rise as did Parliament’s doubt that flying boats were the way forward. The ministry’s plan was that BOAC would operate a fleet of these large flying boats across the Atlantic to the USA. They would be the most luxurious aircraft flying the Atlantic. The twin decks would be linked by spiral staircases and sleeping cabins would all be en-suite. On board there would be a dining room, cocktail bar and even a promenade walk for the passengers to enjoy. BOAC was supportive of the project at first, but after operating its last flying boat service in 1950 interest waned and the airline decided to concentrate on the new Comet and Britannia airliners for its future needs and by 1951 it lost all further interest in the Princess. Undeterred, the Ministry of Supply stated the three aeroplanes would be used by the RAF as transports. But come the following year in 1952 they further announced only the prototype would be completed and the other two would await more powerful engines. All three hulls were well on the way to completion, in fact the prototype was near to its first flight. All work on the second two was suspended.

In August 1952 test pilot Geoffrey Tyson took the first Princess G-ALUN aloft on its maiden flight which turned into a 35 min circular tour of the Isle of Wight. A number of additional test flights were quickly flown with the hope of getting the plane to that year’s Farnborough air show in September, but it only managed to make a brief appearance on press day. A whole year of flight testing would pass with much work being done on the engines and their gearboxes. Farnborough 1953 did see the first and only appearance of the Princess flying boat on the public days. It wasn’t until mid-1954 that all the problems had been ironed out and the aeroplane finally met its design criteria. It had however missed the boat so to speak and the RAF had made it quite clear that like BOAC and most of the world’s major airlines they were no longer interested in operating flying boats.

With test flying completed and no buyers in sight the government could not make up its mind what to do with these three unwanted aircraft that had been bought at great expense with public money. While they mulled it over. the three aeroplanes were cocooned and placed in storage at Cowes and Calshot Spit awaiting a decision about their fate. In the ensuing years there were several suggestions as to what could become of the planes, Aquila Airways made an offer of £3m for them but this was turned down by the government. There was a project by the US Navy who looked into converting them to nuclear power and the two Princesses cocooned at Calshot were partially dismantled in readiness for shipment to the USA, however the project went no further and these two Princesses were scrapped in 1965. Saunders-Roe had even came up with a plan to convert them from flying boats to land based aircraft but the Princesses just sat there wrapped in their cocoons, looking like mummies to small school boys passing on the Isle of Wight ferry.

In 1966 the remaining prototype was to be prepared for sale to American company Aero Spacelines who were looking to build an outsize transport plane for carrying the first stage of the Saturn 5 rocket to Cape Canaveral for NASA. Things were looking up at last. Would this plan finally awake the last sleeping Princess? It was not to be. On removing the cocooning material the airframe was badly corroded having been under wraps for almost13 years. The regular maintenance contract that was meant to prevent this from happening had been cancelled by the government some years earlier most likely to save costs. As a result, the deal fell through and the last Princess was scrapped the following year. Aero Spacelines went on to build the Guppy and Pregnant Guppy range of aircraft. As constructor John Conroy said: “if they had converted the Princess, how would the name Pregnant Princess have gone down with the British government!”

After the 1967 scrapping of the last Princess the fuselage lived on for a number of years as an office and stores at the scrapyard in Southampton. When she was finally cut up a number of her portholes were saved and used on a private motor yacht. Saunders-Roe would build no more commercial fixed-wing aircraft. They did however go on to build a range of hovercraft, the largest being the SR-N4 car ferry. Re-using their experience with the Bristol Proteus this large hovercraft would be powered by four of the large turboprops and operated right up until 2000 becoming the last operator of the Proteus engine in the world.

There we have it, another British airliner project that failed to live up to expectations due to delays, cost increases, government indecision and meddling by the state airlines. This sadly was to become an all too familiar tale over the next couple of decades. The Princess was a great idea and design but realistically it was 10-15 years too late to ever be a commercial success.

‘till the next time. Keith

Registered Charity No. 285809