Comet….grandaddy of the jetliners!

Date….27 July 1949, Place….Hatfield England, Crew… John ‘Cats Eyes’ Cunningham, Harold ‘Tubby’ Waters, John Wilson, Frank Reynolds and Tony Fairbrother. Event… Maiden flight of the world’s first jet powered airliner, the de Havilland DH106 Comet 1. This is the story by Keith Bradshaw of 70 years of the Comet.

Seventy years ago, airline travel changed forever. The Comet and the jet age had arrived. Designed by de Havilland’s chief designer Ronald Bishop it was hoped the Comet would emulate his other great success the Mosquito. Manufacturers could no longer turn out noisy, low-flying piston aeroplanes. If they wanted to keep up with progress the jet was the only way to go and the very first was built in Britain. At the time, the Comet was considered to be three to four years ahead of any rival and its future looked bright.

Powered by four DH Ghost engines, the Comet1 was ordered by BOAC who intended fitting it out with 36 seats and using it on flights to Africa, the Far East and Australia. The BOAC cabin specification even called for separate Ladies and Gents toilets! The Comet 1 did not have the range to fly the Atlantic non-stop but it was hoped a future version of the Comet would be capable of the coveted Blue Ribbon route to the USA.

The new jetliners featured many innovations including powered flying controls, multiple hydraulic systems and a construction which used both conventional rivets and a bonding system known as REDUX bonding. REDUX was an amalgamation of the words Aero REsearch and DUXford as that was where the company’s factory was located. Aero Research became part of the CIGA group who are still based at Duxford today.

After extensive testing of this cutting-edge aeroplane BOAC became the first airline in the world to operate a Jet airliner with paying passengers when on 2 May 1952 their first service to Johannesburg left London Airport in a blaze of publicity. Jet travel had arrived. With de Havilland so far in front of its rivals other companies tried to catch up by whatever means possible. One of the more unusual moves was by Sud Aviation of France who were designing their Caravelle Jet. They signed a licence agreement with de Havilland which allowed them to exactly copy the nose and cockpit of the Comet 1 and use it on their aeroplane. As the Comet1 settled into service, BOAC and its passengers loved the new aeroplane. However flight crews began to comment on the lack of feel from the powered flying controls and were concerned that they could easily over-control the aeroplane making it unstable in flight. Indeed, there was a fatal accident to a BOAC Comet 1 taking off from Calcutta into bad weather where this problem was cited as the possible cause.

However it was in 1954 that disaster really struck when on 10 January 1954 BOAC Comet1 G-ALYP took off from Rome to continue its journey to South Africa. Just by the Mediterranean island of Elba it crashed into the sea killing all on board. As there was no obvious cause, a board of enquiry was set up. Its finding supported the theory that there had been a fire on board. The Royal Navy meanwhile had been recovering parts of the Comet from the sea but before these could be investigated thoroughly the board of enquiry announced its findings and Comet flights resumed.

Comet flights had been suspended for a short time but after their resumption another Comet1 G-ALYY left Rome for Cairo on 8 April 1954 and it too crashed into the sea by Naples, again all souls were lost. This was the third Comet lost within twelve months. The world’s first jet airliner was grounded. This time a board of enquiry was set up under the Royal Aircraft Establishment and the Royal Navy was tasked with recovering all it could from the crash site. Production of the Comet 1 was halted at Hatfield and BOAC parked all its Comets at London Airport and placed them in cocoon wrapping as any return to flight would be a long way off.

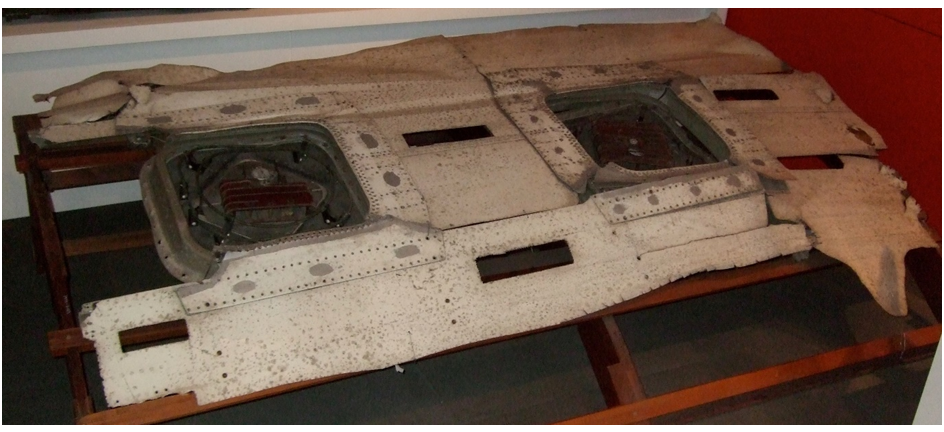

It was during the subsequent investigation and testing of the recovered parts that metal fatigue was becoming the prime suspect. To prove this theory a Comet 1 was placed inside a large water tank at Farnborough and the fuselage subjected to many pressure cycles to replicate the effects of the pressurisation system. The water tank was to cushion any explosion should the structure fail. The fuselage was rigged with a barrage of stress sensors and the engineers were surprised to see just how high the stresses were around the edges of the windows and also on the cabin roof where the ADF aerials were fitted. After 1,836 pressure cycles the fuselage split open. On investigation it was found a crack had developed at a bolt-hole in an escape hatch and the fuselage was not strong enough to stop the crack and opened like a zip fastener. The final report stated that the cause of the crash was due to the fuselage not being strong enough for several reasons including the then lack of knowledge about metal fatigue. Contrary to popular aviation folklore, the window shape was not listed as the cause of the crash.

De Havilland and its competitors used the knowledge so tragically gained to build safer jetliners. De Havilland spent the time after the grounding working on further variants of the Comet. The Comet 2 was mainly based on the Comet 1 but with oval windows and a longer stronger fuselage. These were mainly supplied to the RAF. The Comet 3 was a much longer aeroplane powered by Rolls Royce Avons with a bigger wing and pinion wing tanks giving a greater range. Only one Comet 3 flew as it was only really a trials aircraft for the most successful variant the Comet 4. This version of the jet was 18 feet 6 inches longer than the original Comet 1 and could carry (in the 4C version) up to 119 passengers compared with the Comet 1’s 44. The Comet 4 had the ability to carry even more fuel than the Comet 3 and thus was capable of crossing the Atlantic non-stop west to east.

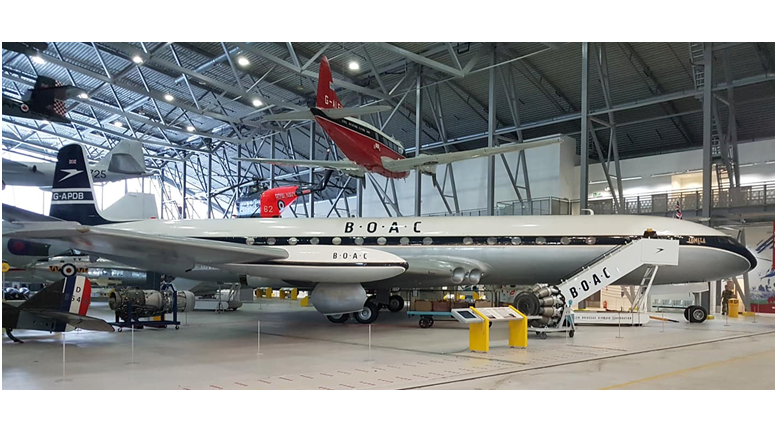

In March 1955 BOAC placed an order for 19 Comet 4 aircraft with the prototype first flying on 27 April 1958, getting its Certificate of Airworthiness on the 24 September of that year. BOAC took delivery of its first Comet 4 the next day. Ten days later on 4 October 1958 the brand new airliner started the first regular transatlantic jet service, beating Pan Am and their Boeing 707s by just a few days. The aircraft that made this historic crossing from New York to London was our very own Comet 4 G-APDB. Two other airlines bought new Comet 4 aircraft, Aerolineas Argentinas and East African Airlines most other major airlines were buying the Boeing 707.

British European Airways bought a version of the Comet 4, the 4B, this had an even longer fuselage but a smaller wing and no wing pinion fuel tanks as it would only be used on short haul flights, the fuselage stretch giving a capacity of 99 passengers. Olympic airlines also ordered this version.

The final true Comet version was the 4C. This used the long fuselage of the Comet 4B coupled with the big wing of the Comet 4 giving it the ability to carry up to 100 passengers over a long range. First flying at the end of 1959, this version found favour with Mexicana, Middle East, United Arab, Sudan and Kuwait airlines.

By the mid-sixties Comet orders were very thin on the ground and by 1965 BOAC had retired its Comet fleet. However many other airlines continued to operate the type up to its last commercial flight in 1981 with Dan Air. For many years Dan Air had been buying up Comets worldwide and at one time owned all 49 of the world’s airworthy examples! It is thanks to them that several Comets found their way to museums including our own PDB which had left BOAC for Malaysian Singapore Airlines before being snapped up by Dan Air and finally donated to us in 1974.

It was however left to a Comet 4C operated by the RAE at Boscombe Down to operate the very last Comet flight when its example XS235 ‘Canapus’ made its final flight with them on 14 March 1997. It did make one more trip when it was delivered to the Cold War Jets Museum at Bruntingthorpe where to this day it can be seen powering down the runaway at their open days.

After all the problems experiencerd by the early Comets, the final design was a good one. When Hawker Siddeley designed a new maritime patrol aeroplane to replace the RAF’s aging Shackleton fleet they took a Comet and grafted a huge pannier on the bottom of the fuselage for equipment and weapons and developed this concept into the Nimrod. Entering service in 1969, the mighty hunter flew on until 2011 when defence cuts retired the fleet even though re-engineered with a new wing and avionics new Nimrod MR4s were waiting to be delivered. So for 62 years Comet variants graced the world’s skies, I think therefore it should be considered a success story.

The Comet was a flawed diamond but the project’s lasting legacy was to not just take airliners into the jet age but also to enable so much to have been learned about high speed/high altitude flight and metal fatigue which has helped today’s airline industry produce such safe aeroplanes.

Happy 70th birthday grandad Comet and thank you for making flying safer.

‘Till the next time Keith

Registered Charity No. 285809